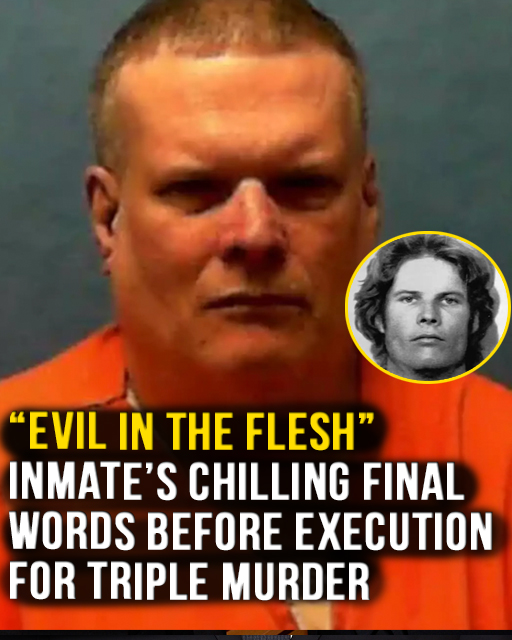

Before taking his final breath on the gurney at Florida State Prison, David Joseph Pittman, who had been dubbed “wicked incarnate” for the brutal murder of three people in 1990, issued some chilling last words to those present at his execution.

On May 15, 1990, driven by what prosecutors described as rage over his wife’s decision to divorce him, Pittman traveled to his in-laws’ home in Mulberry, roughly 40 miles east of Tampa.

After cutting the phone lines, Pittman entered the residence and first attacked his 20-year-old sister-in-law, Bonnie Knowles, stabbing her seven times. He then fatally stabbed her parents, 50-year-old Barbara and 60-year-old Clarence.

Before fleeing in a car he stole from a family member, Pittman—who had reportedly threatened to harm his wife’s family—set the house on fire, followed by the vehicle.

“‘Wicked incarnate’”

“Except for his ex, Pittman wiped out an entire family,” prosecutor Hardy Pickard told jurors during the 1991 trial, as reported by the Tampa Tribune and USA Today.

Polk County Sheriff Grady Judd, who was a major in the patrol division at the time and responded to the crime scene, said he would never forget what he saw.

According to USA Today, Judd referred to Pittman as “wicked incarnate,” adding, “If there’s ever been anyone who deserved the death penalty, it’s David Pittman.”

Troubled Childhood

During sentencing, Pittman’s mother, Frances, testified that her son didn’t speak until he was four and struggled with school, unable to manage his behavior, as reported by the Tampa Bay Times. She described him as a child who was bullied by his peers, sent home on his first day of first grade for disruptive behavior, and pushed through eight years of school despite failing grades.

“To put it simply, he was a child most women would not want to raise,” his mother told the court at the sentencing hearing. “He was hyper. He just kept your nerves on edge all the time.”

Despite his mother’s testimony, Pittman was sentenced to death on three counts of first-degree murder in 1991.

Claims of Intellectual Disability

Over the next thirty years, Pittman’s defense attorneys argued that his execution should be spared due to intellectual disabilities, citing his childhood special education records, an IQ of around 70, and signs of brain damage.

By June 2002, years after Pittman’s crimes, the Death Penalty Information Center noted that federal law prohibited the execution of those with intellectual impairments.

However, in the early 1990s, intellectual disability was not considered a legal barrier to execution. State lawyers pushed back, arguing that Pittman’s claim of mental impairment had been raised too late and should not apply retroactively.

Courts consistently sided with the state, and on September 16, 2025, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected Pittman’s final appeal.